Trans-created :

Ojachito (from Original Hindi)

Foreword

The contemporaneity belongs to the age of the Control Society – a social condition of the life-world constantly living under the threat of surveillance either by the state agencies or those sponsored by the multinational corporates and other similar capitalist establishments. There is no denial of the fact that the regulation of attitudes and behaviours has always been a part of human society since its birth. But, the conglomeration of the state agencies and the corporate capital, aided by digital, electronic and telecommunication technologies, has given rise to a neo-liberal regime of control, which is pervasive yet invisible, and this is especially threatening for the existence of the dissenters’ voices. The global capital and the subservience of the state, which itself seems to have become a corporate establishment/agent being oblivious of its social welfarist nature, is constantly posing threats to the conscious individuals and free-thinkers. The display of the spectacularity flooding across the lives and spaces, resulting in the colonization of the imagination of the general public, is increasingly becoming ubiquitous in nature. Thus, on one hand, the majority of the aspects of the imaginative and lived life, has merely become representational, and, on the other, basic human values, social behaviours and even intrinsic emotions seem to have been shrouded by suspicion, as if, under the gaze of a detective. History has either been misguided and forgotten, or surreptitiously apprehended.

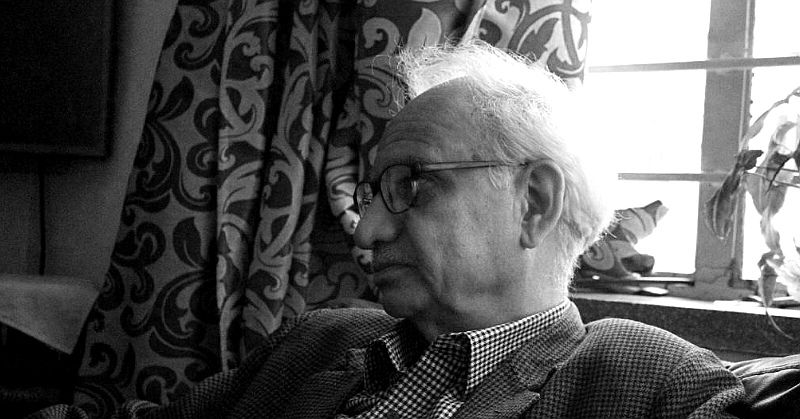

The four poems by Arun Kamal trans-created from original Hindi here are: “Home” (“Ghar”), “Stories” (“Katha”), “At This Burning Ghat” (“Is Shamshan Par”) and “The One Who Witnessed the Murder” (“Jisne Khoon Hote Dekha”) from the anthology titled The World within a Doll (Putli Mein Samsar). All of them are testimonies of at least two phenomena of the ontological life-world that could still retain its originality beyond the afore-mentioned representational value. Firstly, all of them taken together generate an alternative vision of how the life is actually lived, with all hopes and despairs – naked and unabashed. The Preface to the collection rightly points out, “[A]run Kamal has presented the states and phases of the ordinary life.” It is a pity that I am today compelled to categorize the ‘alternative vision’ and the ‘ordinary life-world’ almost synonymously; more so when I think of my literary heritage being anchored by such champions of the mundane as Premchand and Sharat Chandra.

The joint forces of all-permeable intrusion of the global capital, the spectacularity of the spaces, the false consciousness of the mass and a control society aided by a surveillant state have shrouded not only the realist but also any representational value of the ordinary, for that matter, almost in a hegemonic spirit. But, one positive aspect of this phenomenon is that it could offer a renewed yet Herculean responsibility to the conscious writers and thinkers (who can think) “against the grain” to dig out the ‘ordinary’ as ‘alternative’ with the power of that of a Benjaminesque ‘ragpicker’. The second function of the kind of poetry that has been trans-created here serves as an impending resurgence of a “politics of dissent”, at least, by the free thinkers. “Dissent” must be seen as a socially, geo-politically and ecologically significant pattern of thinking with the courage that could say ‘No’ in the face of an organized aggression and plunder of the human/e possession and heritage at both individual and communitarian levels. It will come, definitely, at the costs ranging from marginalization to denial to death. Our nation has been witnessing a similar kind of executions of the rationalists and dissenters for the last few years (Gauri Lankesh died on 5 September, 2017).

The Preface to the collection mentions of this activism in a powerful manner: “The poems (of the collection) perform two functions together: to fiercely represent the continuous degeneration and impoverishment of the human-life, and the penetration into the intrinsic life-world by the political status quo, and to find out those voices and contexts that are in defiance of the prohibition and resistance of the power, and thus being the reality and the support system of the noblest values of life.” The mass consciousness in the contemporaneity is almost reified with the open market system and the pan-nationalist agit-prop rhetorics. Human happiness has become so enmeshed with them that at any attempt to “dare to disturb” it leads to breaks and ruptures in harmony. Ironically, this is leading either to a pseudo-existential mode of living or to a crisis in existentialism itself, as the lived life would always have its share of struggles and melancholies. I hope these poems would provide us with some courage at this time of ‘shadow-wars’ within humanity as they offer us some “Voices of Dissent” amidst an all-encompassing gloominess.

Translator’s Note

In most of the cases, I have tried to follow the spirit of the original poems in Hindi in these trans-creations. I have also attempted to retain the semantic implications as well as the sonority as far as the rhythmic and rhyming structures of the poems are concerned. The quality of a dark noir in “The One Who Witnessed Murder” has bestowed upon the protagonist the heavy burden of memory and a consequent sense of sin so much that it outrightly prohibited me of a harmonious music, and instead, dictated me to go with the spirit of the blank verse. At last and as usual, I have, in some places, taken the liberty with the imageries and metaphors as they appealed to me. This might cause little deviations in the re-created versions of the poems. Yet, I would like to reiterate that I am optimistic of the fact that this act would result in expanding the literary-aesthetic horizons of the poems concerned. In spite of that, an apology to the poet in advance deems fit to be the right course of action in order to preserve my artistic safeguard as a translator.

Home

Don’t wait for the one that has renounced home

Where would he go?

Carrying him which way would the crosswind roam?

Which trench would locate his carcass?

Which pillar of a bridge would mark the remains of his body’s mass?

Will you then be able to identify?

Or, the mole on the thigh by then would only remain a mark to signify?

The balloon that has left for the sky

Who would affirm what has happened to it?

Till the time its footsteps are found

Some unknown shore would get it drowned.

Close your doors

Don’t call me again

Go back home

Which is as rare as oxygen.

The world is not the mother’s womb

Once someone has renounced home

Fails to find the one till his tomb.

Stories

When they would discuss stories of that time

They would say that

Home then used to be the most insecure place

And the most secure was the graveyard.

Then a time arrived

When the entire village was deserted

leaving behind the smouldering stoves,

Then they would say that they saw

A child suckling on her dead mother.

And, once also came such a time

When life made death the prime.

When they would discuss the stories of that time…

At This Burning Ghat

Yesterday where there was water to suffice drowning

Now that’s survived by sands.

The corpse rests on shoulders

Parching the sands beneath

The water still larks afar

Burns scratch the shoulder’s sheath.

In any case, the river flows lifeless

That side there is a thicker course

Watermelons grow upon

The stretch-less sands that lie across.

Who remembers the depth of the water here

Where the boat sank!

A child runs splashing

Sands sparkle beneath the shallow tank.

Fear grapples when I walk upon the dry sand-bed

As my memory haunts the river once flooded.

Yet, keep walking, a little farther. . .

I shall drop you where there remains some water

The best place to be at this burning ghat, rather.

The One Who Witnessed the Murder

No, I haven’t seen anything

I was inside – stirring chick-pea flour with water –

No, I haven’t seen anybody. . .

Would you please call Sameer?

I called out – Sameer

And, he came running – as if, deserting

A game half-played – panting. . .

No, no – will keep quiet – I have also my children inside. . .

He was still such a young lad

Like a sleepy mulberry. . .

Soft like an East Indian walnut. . .

His mouth still retained the fragrance of his mother’s colostrum.

Alas! Why did I call him!

Why did the death choose me to be the butcher’s block!

No, nope, I don’t know . . . I haven’t seen anything. . .

I haven’t seen anybody. . .

There were two of them, one was

who called me probably sister, or, may be, aunty

There was light, there was dark: there were

moths hovering around the bulb

I was about to turn back

And, oh, suddenly. . .

Sameer, I ran (calling) – Sameer. . .

Milk and blood

Blood

No, no, never, nothing. . .

And, I know everything

I know all of them

Who spilled the blood

I recognize each and every sole of their boots

Gradually, I could see the gunpoint turning towards me. . .

Gradually, turning omnidirectional. . .

***

Ojachito is a nobody. His absence may be felt at: sovantamluk08@gmail.com